First, two stories that highlight two different sides of elephant hunting.

In 2005, Meridio was guaranteed to win a deal worth $15m+. Meridio was a small electronic documents and records management (EDRM) startup whose software ran inside some of the world’s most secure organizations: from banks to oil & gas companies to branches of government and the military. One of its happy customers, the UK Ministry of Defense (MoD), was looking to modernize its infrastructure in a massive IT procurement worth billions. Each of the two integrator consortia shortlisted for the deal had designed Meridio into the solution. It was the largest secure SharePoint deployment in the world at the time: a great proof point of the quality and scalability of Meridio’s software. The future looked bright.

Meridio did win the deal and get the money in the end, but the process nearly killed the company:

- The product roadmap and development prioritization became more complicated.

- Supporting the two fiercely competitive integrator consortia required staffing up teams with semi-duplicated responsibilities: a significant distraction and increase in burn far ahead of revenue.

- Once the MoD deal was awarded to one of the consortia, Meridio had many employees it couldn’t put to productive use quickly. The resulting layoffs impacted culture.

The UK MoD deal was important for Meridio — it influenced the 2007 sale of the company to Autonomy, now part of OpenText — but it was less impactful from a valuation standpoint than the company imagined it’d be. Winning the deal came at the expense of distraction and operational inefficiency, both of which affected growth in other areas of the business. Also, there never was another deal like it.

And now for story #2. In 2014 Life360 hit gold. After 18 months of lengthy negotiations, Life360 landed a $50m investment deal from ADT, the global leader in Home Security, coupled with a strategic joint product development opportunity that could net the company tens of millions of dollars in revenue. The team was dancing on rooftops!

In 2019, long after the commercial deal was dead in the water, Life360 decided to go public early (compared to its peers), and one of the considerations was ADT’s significant position as an investor in the company. Further, after years of development that sucked, at times, half of our engineering team’s bandwidth, the product we launched was discontinued and made no contribution to our business. When the company struck the deal employees were initially very excited. They believed that the organization they were working with would be as devoted to the strategic deal’s success as their small startup was. Three management team changes later, it became clear that the deal, which was one of the highest priority items on Life360 plate, was a pretty low priority for ADT. New execs at the company didn’t feel a real commitment to it, and a Private Equity acquisition coupled with organizational changes didn’t help much either.

Everything is easier in hindsight, but Life360 could have avoided this. Luckily, the deal didn’t end up being a company killer and the other parts of the business helped Life360 cement a great spot as a public company. It’s probably fair to say Life360’s success happened despite the ADT deal, not because of it.

What it is?

“Elephant Hunting” is a buzz term describing the practice of targeting deals with very large customers. For example, hunting an elephant in the context of a startup could be a seed-stage company targeting the likes of Google or AT&T as a customer in a million-dollar deal. These customers can provide large contracts, but they can be hard to catch and require large teams to tackle. With business-to-business (B2B) startups, there’s almost nothing more exciting (or seductive) than hunting and bagging an elephant-sized deal. It can produce huge revenue growth, provide you with highly leverageable customer references, and it’ll excite investors. Once you hunt down an elephant, it can feed many mouths (and egos) at the company for a long time. What could be better?

Be warned: the pursuit of elephants can be a dangerous game. If you fail to “kill the elephant” it might well be the one killing you. Unlike young and dynamic startups, elephants are organizational dinosaurs and striking a deal with an elephant will require your entire team — from sales to engineering — to engage with the elephant at different levels of the organization. This engagement happens over months, sometimes years. Even if you succeed in getting an elephant, you may get less benefit than you expected, as the cases of both Meridio and Life360 demonstrate.

Why it matters?

Elephant hunting can bring your company down on its knees. Here are some perils to be aware of:

- No repeatability. Elephants are hard to catch and often there aren’t enough of them. Meridio never found another UK MoD. Life360 never found another ADT.

- Heavy operational burden. When you pursue and, later, land an elephant, it’s tempting to put all your resources into serving them. But this can lead to neglecting other clients and missing out on potential opportunities. Both Meridio and Life360 suffered operationally while selling and, later, servicing their respective elephants. Elephants may demand extended payment terms or lower prices, which can put a strain on a startup’s finances. It’s important to carefully consider the financial implications of taking on an elephant client.

- Missed learning opportunities. When you and your team are laser-focused on one client you might be missing the forest from the trees. As a startup, you seek scalable solutions that matter to most potential customers you want to serve. More feedback is better, and getting feedback from just one elephant makes it harder to identify the scalable, repeatable, products that your target audience needs.

- Overpromising and underdelivering. In the rush to impress an elephant, startups may make unrealistic promises they can’t keep. This can damage their reputation and lead to the loss of the elephant and future clients. Elephants have tall expectations for products and services delivered, as well as a web of requirements across legal, compliance, cybersecurity, etc. that smaller companies may be incapable of servicing well.

- Compromising your identity. When a startup lands an elephant, it’s easy to become absorbed in their world and lose sight of your own identity and values. This can lead to compromises that go against your startup’s mission and culture. Note, for example, how many big tech companies have had to compromise to do business in China.

- Losing control. Elephants may have their own demands and expectations that clash with a startup’s way of doing things. This can lead to a loss of control and autonomy, as the startup becomes beholden to the elephant’s whims. On the partner/channel side, this relates to the platform risk anti-pattern. In conclusion, while landing an elephant can be a huge boost for a startup, it’s important to be aware of the perils that come with it. By maintaining a balance, staying true to your values, and carefully considering the operating implications, startups can avoid the dangers of elephant hunting and build sustainable growth.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is relatively straightforward. Here are a few signals that you might be spending too much time elephant hunting or are getting sucked into the Savannah:

- Are you and your sales team spending most of your time focused on one deal with a big enterprise client? Has this been going on for an extended period?

- Are you increasing spend ahead of revenue more than what you’d normally do for just one or two deals?

- Is a significant chunk of your engineering team’s bandwidth focused on building custom features for one big customer? Does it feel like this customer is essentially dictating your roadmap for the foreseeable future? Do you find yourself having to promise steep SLAs and help desk hours that you know your existing team can’t support now or in the near future? Startups often do need to stretch to deliver, but if your team feels that servicing the elephants will consume the entire company, they’re probably right.

Misdiagnosis

A common misdiagnosis stems from not fully understand or realizing the scope and bandwidth consumption of Elephants. Often, it’s easy for the team to get excited about big deals and they tend to look the other way. Developing and delivering products to Elephants comes with significant overhead, longer sales cycles, lower win rates, and, often, requirements and standards that don’t make a positive impact on the joint outcome, but suck a lot of time and energy from everybody in the room.

Put together KPIs and tools to help you measure the impact elephant hunting has on your Sales and Engineering teams and make data-based decisions.

If your startup is investor-backed, remember that your job is to grow equity value. Revenue, profits and growth are pieces of how equity value is determined. Ask yourself whether the pursuit or even the winning of an elephant will have a meaningful positive impact on equity value given all the positive and negative externalities.

Refactored solutions

Once diagnosed, the refactoring of this anti-pattern very much depends on the set of challenges and opportunities your company has at hand. A few ideas on how to make the most out of Enterprise customers without consuming your entire (small) organization in the process:

- Try to strike a smaller, multi-phase, deal with the Elephant. That would help both sides build confidence and capabilities to better serve each other.

- (Artificially) Limit the resources devoted to elephant hunting. Be ruthless about this with your sales and bizdev folks. They’re likely to gravitate towards elephant hunting — these deals tend to be very exciting.

- Continuously measure and analyze how much your team spends on custom work (especially non-repeatable deals and non-productizable work). It might put a strain on your relationship with the Elephant customer, but good Sales and Customer success teams can help strike a balance and set expectations.

- Do you have enough slack to sign a deal with an Elephant? One good rule of thumb is assuming that deal will require twice as much resource and time compared to your original expectations. If that’s the case, would you still execute on the deal?

When it could help?

Does this mean you should never try to hunt elephants? No, but it does mean you should think very carefully about it, and be prepared to answer a few questions:

- Where does elephant hunting fit in your sales and growth strategy; near vs. longer term; lower-hanging fruit vs. higher up your sales tree?

- How many elephants are there for you to hunt? Is that a real market niche for your business?

- Do you have the human resources to hunt and satisfy elephant-sized customers?

- Do your sales, engineering and customer success people have the skillsets and experience to satisfy this species of customer?

- Does your CEO have the bandwidth and skill to take down the elephant? This strategy often demands an inordinate amount of the CEO’s time. Which of the CEO’s other responsibilities might suffer?

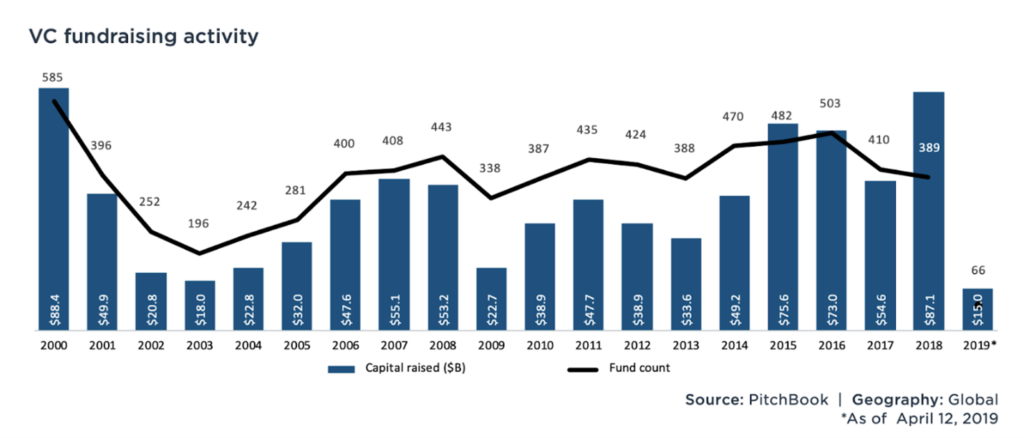

- Does your company have the financial resources to survive and thrive in the face of typically slow decision and purchase cycles? Will investors give you (relatively) cheap cash so that you can wait for the revenue?

For many startups, the transition to spending more time on Elephant hunting is part of the startup journey from childhood to adolescence. If you have good answers to the above questions, a more mature product that is ready to scale, you and your team might be ready to make the move, but tread carefully so you don’t end up being yet another victim on the plains of the Serengeti.

Co-authored with Simeon Simeonov. More startup anti-patterns here – https://blog.simeonov.com/startup-anti-patterns/